The author is the professor of practice and senior director of the Oregon Economic Forum at the University of Oregon and the author of Tim Duy's Fed Watch.

The Federal Reserve eschews balance sheet policy – changes in the amount or composition of assets held by the central bank – in the early stages of its plans to normalize the extraordinary monetary policy it instituted in the wake of the financial crisis. Instead, the Fed’s normalization plans currently focuses on raising the federal funds rate. But the central bank may need to use both rate policy and balance sheet policy simultaneously to reach the objectives of its dual mandate – or price stability with maximum sustainable employment – while sustaining a financial environment consistent with those objectives.

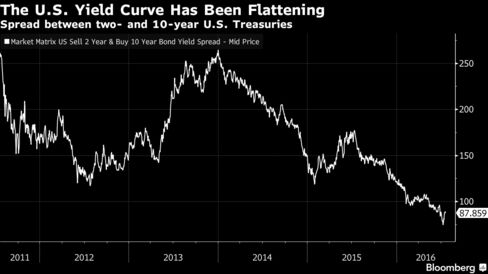

The flattening of the U.S. yield curve as investors see little chance of rates rising in the longer term should serve as a red flag that their focus on short-term interest rates may be doomed to failure.

Source: Bloomberg

One of the defining features of this tightening cycle is the same as the cycles that came before – the yield curve is flattening, and very quickly. The spread between 10-year and two-year U.S. Treasuries has collapsed to 88 basis points at a time when the federal funds target rate is 25-50bps. This suggests that the Fed actually has very little room to raise short-term rates. If additional rates hikes compress the yield curve further, the capacity for maturity transformation – effectively the process of borrowing on shorter time frames to lend on longer time frames – will soon be compromised.

Federal Reserve Governor Daniel Tarullo sees the threat. Speaking with the Wall Street Journal, he said:

Tarullo said he didn't think that the worry that low interest rates may fuel asset bubbles was an “immediate concern.”The Fed governor, who is the quarterback of the Fed's efforts to regulate banks, questioned whether raising rates would ease financial stability concerns in an environment where the market was pessimistic about the economic outlook.“If markets do regard economic prospects as only modest or moderate going forward, then raising short-term rates is almost surely going to flatten the yield curve, which generally speaking is not good for financial intermediation, and in some sense could exacerbate financial stability concerns,” Tarullo said.When rates are low, regulators should pay more attention to financial stability issues "but it doesn't translate into 'therefore raise rates and all will be well,'" he added.

Some of Tarullo's colleagues at the Fed are pushing for rate hikes sooner rather than later on the basis of two economic narratives. The first essentially collapses to a Phillips curve story. In other words, as slack in the labor market decreases, inflationary pressures rise. To stem those pressures, the Fed needs to raise rates early, especially if they want to achieve a slow pace of subsequent rate hikes.

The problem with this story is that the Phillips curve is flat as a pancake, hence the calls for early rate hikes to quell inflationary pressures fall on some deaf ears around Constitution Avenue. This is especially the case after a long period of below target inflation and, perhaps more worrisome, evidence of declining inflation expectations. It is simply hard to build much support for the "we need to raise rates because of inflation" case in this environment.

In the absence of a strong inflation argument to justify rate hikes, some Fed policymakers are leaning more heavily on a second narrative, the financial stability angle — the fear that low rates foster asset bubbles or, perhaps worse, dangerously high levels of leverage within the financial sector.

For instance, San Francisco Federal Reserve President John Williams recently said:

"The risk I think we face in waiting too long, or waiting maybe as long as some of these market expectations are, is that the economy is already pretty strong and if we wait too long in further removal of accommodation I do think imbalances will form more generally. It could show up as more inflation pressures down the road, we're not seeing those yet, but I think that you do see some of this in terms of real-estate markets and other asset markets which are being priced to perfection based on an outlook of very low interest rates. You are seeing extremely high asset valuations in real estate, commercial real estate, the stock market is very strong relative to fundamentals. That is a natural result from low interest rates, that's one of the ways monetary policy affects the economy. But if asset prices, real estate prices, continue to go further and further away from longer-term fundamentals I think that creates risk for the economy, I think it creates risks eventually for the financial system."

Tarullo will likely push back against this line of thought. Raising interest rates alone may not alleviate financial stability concerns. In fact, they may aggravate those concerns if the yield curve continues to flatten. In contrast, consider the implications of a potential policy path charted in June of 2015 by New York Federal Reserve President William Dudley:

"An important aspect of current financial market conditions is the very low bond term premia around the globe. If a small rise in short-term rates were to lead to an abrupt increase in term premia and bond yields, resulting in a significant tightening in financial market conditions, then the Federal Reserve would likely move more slowly — all else equal. As an example, consider the experience of the 1994-95 tightening cycle. Bond yields rose sharply and the Federal Reserve tightened less than what was ultimately priced in by market participants. Conversely, if term premia and bond yields were to remain low and the economic outlook suggested that financial conditions needed to be tighter and a rise in short-term rates did not generate this outcome, then the FOMC would likely need to raise short-term rates further than anticipated. The 2004-2007 tightening cycle might be a good example of this. The FOMC ultimately pushed the federal funds rate up to a peak of 5.25 percent, in part, because the earlier rise in short-term rates was generally ineffective in tightening financial market conditions sufficiently over this period."

Dudley, at least last year, believed that during the 2004-2007 cycle the Fed needed to push harder on the short end of the curve because the long end wasn't responding. In the process, the Fed inverted the yield curve, which only exacerbated the financial crisis along the lines of Tarullo’s thinking. Policymakers need to think carefully before they create conditions that interfere with maturity transformation and hence financial intermediation. Following Dudley's 2015 advice now by raising short rates to quell nascent financial stability problems would be a complete disaster. He probably realizes this.

But note too that Dudley looks disapprovingly on the 1994-1995 cycle. For policymakers at the Fed, that cycle has left an indelible mark on their psyche. The just can't shake it. And 2013's "taper tantrum," or the steepening of the yield curve in the wake of former Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke's hints that quantitative easing was ending, revived their fear of a 1994 repeat. The Fed doesn’t like a steep yield curve, but they won’t like a flat one either.

So what's a central bank to do? They try to exit this quandary through forward guidance — attempting to control the long-end of the curve by signaling their intentions for the short-end. This does not appear to be working; the interaction of policy and guidance are flattening the curve further but leaving short-term rates near zero. As it stands, it is all too easy to see the economy gaining sufficient momentum to prompt the Fed to tighten further, but that tightening would quickly invert the yield curve and send the credit creation process on a recessionary trajectory.

Tarullo provided another path for the Fed to follow in a 2014 speech:

"Finally, it may also be worth considering some refinements to our monetary policy tools. Central banks must always be cognizant of important changes that may result in different responses of households, firms, and financial markets to monetary policy actions. There is little doubt that the conduct of monetary policy has become a good deal more complicated in recent years. Some of these complications may diminish as economic and financial conditions normalize, but others may be more persistent. Central banks, in turn, may want to build on some recent experience, adapted for more normal times, in addressing the desire to contain systemic risk without removing monetary policy accommodation to advance one or both dual mandate goals. One example would be altering the composition of a central bank's balance sheet so as to add a second policy instrument to changes in the targeted interest rate. The central bank might under some conditions want to use a combination of the two instruments to respond to concurrent concerns about macroeconomic sluggishness and excessive maturity transformation by lowering the target (short-term) interest rate and simultaneously flattening the yield curve through swapping shorter duration assets for longer-term ones."

In this example, he suggests responding to financial market excess in a weak economy by flattening the curve via balance sheet tools while lowering rates. The lesson, however, is more general. The Fed needs to think of policy in terms of using two tools — rates and balance sheet — simultaneously. Forward guidance alone might not be sufficient to allow the rate tool to mimic the impact of both jointly. In the current environment, should the Fed want to increase rates to tighten policy but at the same time be concerned about excessive flattening of the yield curve, they would need to sell long-dated Treasuries from their portfolio to normalize policy. Depending on conditions, this may be in concert with rate hikes at the short-end.

Bottom Line: The Fed needs to remember that how they got into this policy stance may offer a lesson for how to get out. Policy makers cut rates to zero and then instituted quantitative easing. Now they should consider selling assets before raising rates. Or, at a minimum, utilizing a mixed strategy of rate hikes and asset sales. The objective of meeting the Fed's mandate in the context of maintaining financial stability may be unattainable using the interest rate tool and associated forward guidance alone. Unfortunately, the Fed does not appear to be debating the policy mix — at least not in public. They remain focused on interest rates, delaying balance sheet policy to a later date. On the current trajectory, however, that later date may never come.

For all your mortgage needs you can reach Bobby Darvish of Platinum Lending Solutions.

For all your mortgage needs you can reach Bobby Darvish of Platinum Lending Solutions.

No comments:

Post a Comment