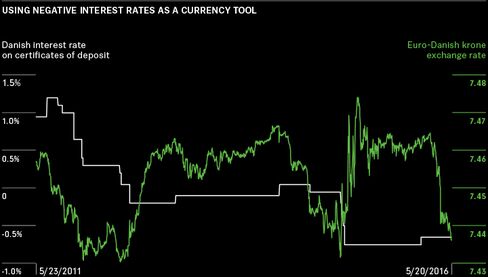

Central banks are doing what was once unthinkable. Will it save their economies?

It was long thought that

interest rates could never go below zero. People would surely hoard

cash before they paid banks for the privilege of holding it for them.

But this year the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan, and others

have officially ventured into negative interest rate territory. It’s a

bold experiment in economic stimulus—with big risks to global investors.

Right now there are a whopping $10 trillion in total

negative-yielding sovereign bonds outstanding worldwide, according to a

report by Fitch Ratings. Just as startling: 26% of the total value of

J.P. Morgan’s global government bond index has a below-zero interest

rate. The dynamic has even trickled into the corporate sector, where

there are more than $300 million worth of negative-yielding bonds.

That has caused serious headaches for money managers, especially pension funds and insurance companies in Europe, which must fight over the increasingly scarce supply of relatively safe but positively yielding assets. The U.S. is also affected, even while the Fed maintains positive rates. According to Alex Roever, head of U.S. rate strategy at J.P. Morgan

JPM

-4.13%

, 48% of the positive-yielding sovereign debt not held by central banks is U.S. Treasuries, meaning competition to buy U.S. debt is tougher than ever before, and demand could drive Treasury rates even lower.

All this would be manageable if the

negative rates were seriously juicing the European and Japanese

economies. But there’s not much evidence that it’s actually leading to

more lending or higher growth. Meanwhile, signs of distortions in the

system are growing, like data showing that sales of cash safes are

surging in Japan, as households lose confidence in the banking system to

protect their savings.

Torsten Slok of Deustche Bank Securities

argues that better results would come from targeted stimulus of

governments. Central banks have done what they can, he says, and “now

the politicians need to do their job.”

Amid Brexit, China Gets a Dose of Economic Worry Along With More Power

As Chinese leaders tally up the losses and gains from Brexit, they likely have mixed feelings.

Beijing may be 5,000 miles away from London, but China cannot escape the shock waves of Brexit.Prior to the June 23 referendum in the United Kingdom, Chinese leaders had maintained a studious silence on the issue because of their long-standing policy of non-interference in other countries’ domestic affairs. Now that the British voters have spoken, Beijing has to take a serious look at how Brexit will affect its economic and geopolitical interests.

Economically, Brexit is terrible news for China. Even though the UK, which had $78.5 billion in bilateral trade with China in 2015, is not among China’s top trading partners, Brexit could have an outsize impact on China’s future export performance.

If there is one message broadcast to the world by Brexit, it is the end of globalization as we know it. Political leaders in Western countries will likely roll back free trade in response to the anger and frustrations of their voters who have felt threatened, if not victimized, by globalization. As the greatest beneficiary of globalization and the world’s largest exporter, Beijing could see its future economic prospects dim as the world retreats from free trade and China’s export engine sputters.

The anticipated adverse consequences of Brexit for the UK economy will also force China to readjust its commercial strategy in Europe. In the last few years, Beijing has been wooing London with investments and potentially lucrative commercial opportunities. In his visit to the UK last year, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced deals worth $57 billion. Many Chinese companies have made the UK one of their favorite destinations of direct investment. In 2015, Chinese companies completed 22 major acquisitions in the UK. The biggest was the $9 billion purchase of a 33.5% stake by China’s General Nuclear Power Corporation in Britain’s Hinkley Point nuclear power plant.

If the UK economy deteriorates because of the uncertainty and loss of access to the EU market following Brexit, the value of Chinese investments will be impaired. Even more worrying is that should Brexit fatally damage London as a premier global financial center, China will have to shelf its plan to use London as a linchpin for the “internationalization” of the Chinese currency, the renminbi. In 2015, Beijing took several initial steps to execute this strategy. The People’s Bank of China floated 5 billion yuan-denominated bonds while the Agricultural Bank of China, a major state-owned bank, sold $1 billion in dual currency bonds in London. In the aftermath of Brexit, many major global banks may move their capital market operations out of London, which will lose its luster as a global financial hub. China needs to look for an alternative.

Nevertheless, China’s potential economic losses could be offset by some political gains from Brexit. Ideologically, Brexit is a godsend for China’s propagandists, who have lost no time in portraying the event as a convincing example of the dysfunction of democracy. Geopolitically, China could also benefit handsomely from the aftershocks of Brexit. Until roughly a decade ago, Chinese leaders viewed European integration positively since they believed that a strong Europe would be a counter-weight to American hegemony.

However, as rapid economic development has made China the world’s second-most powerful country, Chinese leaders have rethought European integration. A united and strong Europe is no longer in China’s interest because of the risk that the United States and Europe could form a strategic alliance to gang up on Beijing in the same way they contained the Soviet Union.

Subsequently, China’s European strategy has undergone a subtle but important change. It has shifted to cultivating ties with individual European countries and often pitting them against each other. So far, Beijing’s new strategy has been a resounding success. And the EU has not developed a unified response to Beijing’s “divide and conquer” tactics. Nearly every European country has its own China policy, which subordinates human rights concerns and security issues to commercial interests. It is instructive that these days no European leaders dare to meet the Dalai Lama anywhere in their countries. It is even more revealing that when China announced the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) last year, all the major European countries, led by the UK, rushed to join, apparently against the wishes of the United States.

Now with British voters opting to exit the EU, the UK will be weaker, and the EU will be even weaker. A diminished EU will not be able to stand up to China, and its internal woes will reduce its value as a strategic partner of the U.S.

As Chinese leaders tally up the potential losses and gains from Brexit, they likely have mixed feelings. If they could choose, Beijing’s pragmatists would undoubtedly prefer the certainty of the pre-Brexit world.

Minxin Pei is a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College and the author of China’s Crony Capitalism.